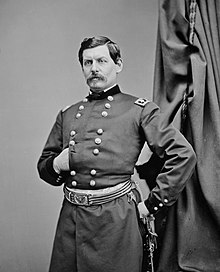

CS General Robert E. Lee US General George B. McClellan

Following the striking victory at the Second Battle of Manassas in late August 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee decided to take his Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into the border state of Maryland. This was done to give Virginia some relief from the ravages of war, put added pressure on the Lincoln administration, and, it was hoped, give an opportunity for Maryland Confederate sympathizers to come out of the woodwork in support of the cause.

Overview Map of the Maryland Campaign of September 1862. [Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com]

Robert E. Lee and his force splashed across the Potomac River from 4-7 September. A corps of 24,000 under CS General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson was sent to capture Harpers Ferry with its garrison and armory -- which was accomplished on 15 September 1862. Jackson captured 73 artillery pieces, 11,000 small arms, 200 wagons, and 12,500 men -- only losing 286 of his own troops in doing so.

Meanwhile, Union General George B McClellan had assumed command of all Union forces around Washington, DC -- not only his own Army of the Potomac, but those remnants of US General John Pope's Army of Virginia, which were now added to the Army of the Potomac. McClellan went in pursuit of Lee, but with his customary caution and slowness. It was this lethargy that Lee counted on, as he had divided his much smaller army into several pieces stretching from Harpers Ferry across the Maryland countryside.

On 13 September, Lee's entire campaign plans, Special Order No. 191, fell into the hands of the Union high command -- somehow being left at an abandoned campsite. Even the cautious US General McClellan saw a chance, and he moved to strike the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia while still spread apart. The Union Army of the Potomac needed to force its way across a ridge called South Mountain in order to fall upon the divided Southern force.

On 14 September 1862, the Battle of South Mountain unfolded between a couple Union Corps from the Army of the Potomac and a couple Confederate Divisions from the Army of Northern Virginia. The Confederates held their ground, falling back that night, having bought time enough for Lee to asssemble his army at Sharpsburg, Maryland, along the banks of the Antietam Creek.

Here is the NPS description of the Battle of South Mountain: http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/md002.htm

The Battle of Antietam (known as Sharpsburg by many in the South) would be fought on 17 September 1862 between Robert E. Lee's 38,000 man Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, and George McClellan's 75,000 man Union Army of the Potomac. Lee's force hunkered down along a line stretching from north of Sharpsburg, around the old Dunker Church and Corn Field, southeast to the Bloody Line, and finally along the Antietam Creek itself. Jackson commanded the left wing, Longstreet the right, as at Second Manassas. Lee had all of his divisions on the field that morning, save that of CS General A.P. Hill still coming from Harpers Ferry, whose arrival would be critical.

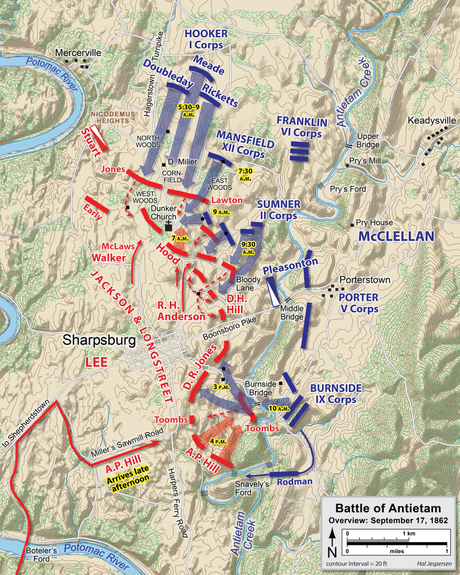

Overview Map of the Battle of Antietam. [Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com]

The Union Army launched a series of assaults, essentially beginning on the Confederate left flank (near the Dunker Church), and rolling to their right flank, ending at Burnside's Bridge on the Antietam. From the Union perspective, the attacks came from the right to the left flanks. The Union Corps attacked in this order through the day: I Corps of Hooker, XII Corps of Mansfield, II Corps of Sumner, and IX Corps of Burnside.

All day long the Confederate host withstood these attacks, sometimes at horrific cost. When the IX Corps of US General Ambrose Burnside finally forced a crossing of the Antietam Creek, it seemed as though the Union army could finally turn Lee's flank and break the exhausted Confederate host -- but the division of A.P. Hill arrived in the nick of time to stabilize the Army of Northern Virginia.

A fanciful print of the Battle of Antietam around Burnside Bridge by Kurz and Allison.

The battle on the field would be a stalemate: Lee had held his ground, but barely. The Union Army of the Potomac lost 12,400 casualties, while the Confederate Army of the Northern Virginia lost 10,300. Of these numbers from both armies, 3,600 in total were killed. This was the bloodiest single day of the war.

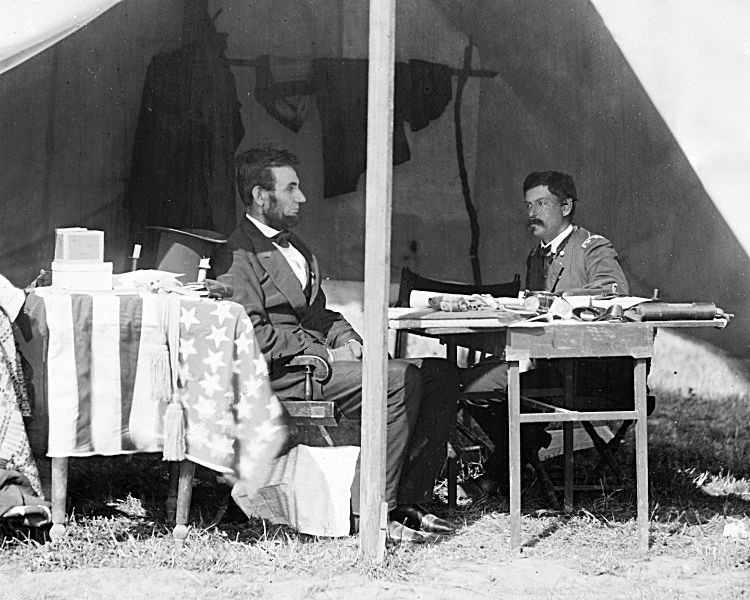

US President Abraham Lincoln meeting with US General George B. McClellan after Antietam. Two year later, these would be rival Presidential candidates for the GOP (Lincoln) and Democrats (McClellan).

Ultimately, however, Lee would have to withdraw back to Virginia, ending his invasion of Maryland, and paving the way for President Abraham Lincoln to announce his plan to release the Emancipation Proclamation -- freeing those slaves in Confederate, but not Union, held areas.

Here is a link to the NPS account of the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg): http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/md003.htm

This is a link to the Antietam National Battlefield, well worth a visit: http://www.nps.gov/ancm/index.htm

Live well!

An excellent summation of the battle. Within concise limitations, the notes which you included cover all of the major effects/points of the battle.

ReplyDeleteTwo points I wanted to share which I have always found very interesting:

First, Lee ought to have been able to fight the battle with at least 55,000 men. He began the campaign with this many, but it seems that many Confederates did not have their heart in the invasion, for many refused to cross the Potomac River, and others later deserted or straggled as the army pressed on. Historical evidence suggests that at this stage in the war, the Confederate soldier still wrestled with the idea of war as defensive only . . . they were OK fighting to defend their own lands, but failed to see the defensive purposes behind an invasion of the North.

Second, the brilliant defense conducted by Lee, Longstreet, and Jackson overshadows the simple fact that Lee put his army in a horrible, HORRIBLE position for a battle. A cursory look at the map above shows that the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) rested in a large bend of the Potomac River. In the event that his lines broke, Lee's army would have found it nearly impossible to retreat, their flanks and rear bordered by the great river. Thus while McClellan exercised an unnecessary degree of caution, Lee exercised an unnecessary degree of risk . . . losing a battle in his current position would have meant his army's total destruction, or close to it.

~C. Paul Martin